Travelling is a part of competitive sport and is an issue that most athletes deal with on a regular basis. Non-athletes may not appreciate just how stressful travelling can be, particularly when it is combined with the demands of training, practice and competition schedules. I’ve learned that travel is especially more stressful for individuals who like to maintain a regular routine. This includes athletes who like to eat at regular times, train at regular times, sleep, etc. To make things worse, crossing time zone’s can add further issues by effecting sleep patterns and disturbing circadian rhythms.

I’m sure if your athletes are open and honest enough, they will be able to communicate any issues they’re experiencing as a result of the travel. However, there’s evidence to show that HRV monitoring is capable of reflecting the time course of individual adaptation to travelling via changes in autonomic activity in healthy folks (Tateishi & Fujishiro 2002, Tateishi et al. 2000). Taken with perceived stress and fatigue, an objective measure such as HRV may provide coaches a more complete picture of their athletes response to the stresses associated with travel.

Brief Research Review

Dranitsin (2008) investigated the effects of travel across 5 times zones and acclimatization to a hot and humid environment in 13 elite junior rowers. The athletes were monitored during a training camp in Kiev for 9 days and during training camp in Beijing for 17 days before and during the Junior Rowing World Championship. HRV was collected daily in the mornings after waking and bladder emptying with a Polar S810i (presently the RS800). Data was collected for 5 minutes supine followed by 5 minutes standing.

HRV parameters remained relatively unchanged after relocation to Beijing until the 3rd day. At this point, standing HRV values decreased until day 6 at which point they returned to baseline. Supine HRV did not show any significant changes until the 8th day of acclimatization. Parasympathetic measures (RMSSD, SD1 and HF) trended upwards in the standing position in response to 3 days of competition. The authors looked at correlations between HRV indices and training load, humidity, etc., but I will not discuss them. With all of the factors involved it would be very difficult to attribute a change in HRV to a specific variable. Overall, it was interesting to see a lag in the HRV response to the change in time zone and climate. The increase in parasympathetic HRV parameters in response to competition likely reflect fatigue although this is not discussed.

Botek et al. (2009) had a case study published investigating the effects of travel across time zones in two elite athletes; a male decathlete and a female swimmer. HRV data was collected upto 10 days prior to their flights and for an additional 8 days after relocation. HRV was measured with a VarCor PF 7 system in both supine and standing positions. Training load was prescribed based on recommendations from the VarCor PF7 software analysis (similar to OmegaWave in a way).

In athlete A (male, decathlete), parasympathetic indices of HRV decreased well below baseline on the day of the flight and remained suppressed until the 4th day after relocation. In athlete B (female, swimmer), HRV remained at baseline until the third day, at which point it decreased significantly. HRV was not recorded every day in athlete B but it appears that HRV trended back toward baseline in the subsequent days. The author’s mention that athlete B experienced larger than normal drops in HRV in response to familiar training which is interesting to note. The results from this case study suggest that HRV responses to travel across time zones are individual. Information about training load and manipulation based on HRV is presented, however it would’ve been nice to see discussion on how the athletes performed in competition as this is ultimately what matters most.

Personal HRV Data from Travel

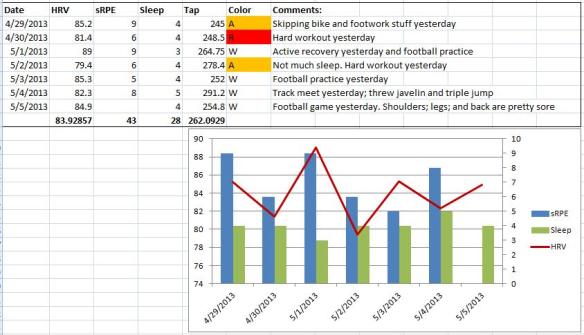

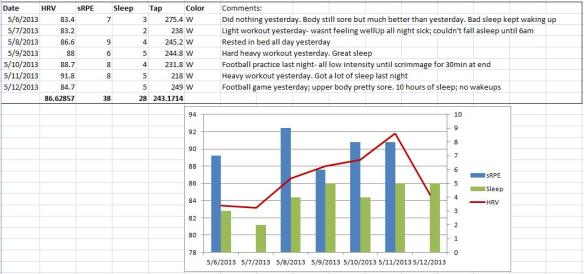

Below I’ve posted my HRV data from the past 4 weeks that involved considerable travel. The comments provide details of what was happening on a day to day basis regarding location, training, etc.

“Routine” implies I’m at home following my regular routine, “Away” obviously implies that I’m out of town, not following my routine.

Toward the end of week 1, I traveled North-East for a little over a week. I returned home only for a few days at the end of week 2 before I headed South-West to Vegas for the NSCA conference.

Week 1 – Best representation of baseline. HRV decreased on day 1 of travel.

Week 2 – Very little training this week. HRV appears most impacted from a night of drinking and again after my birthday which I attribute mainly to my eating.

Week 3 – The scores toward the end of the week are deceiving as the green indication indicated baseline/recovery. However, after very little sleep, I woke up and performed my measurement while I was barely awake. I could have fallen asleep standing if I shut my eyes. Furthermore, with the time difference and changed sleep pattern, my HRV measure would’ve been performed at an unusual time which can impact scores. The next day after returning from Vegas I slept for 10 straight hours and woke up with the highest score I’ve had in a long time. Clearly I was in recovery mode. I opted to go for a long, very low intensity walk (to the tune of “The Very Best of Cat Stevens” every single step of the way) and held off on training til the next day.

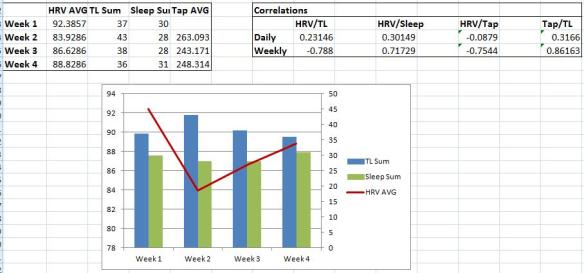

Week 4 – Upon returning home and resuming my training, you can really see the effects of the last few weeks. Moderate workouts (low volume with moderate intensity) were tough and caused large drops in HRV with slow recovery. Additionally, and as expected, strength was down. This is due to both the travel (and associated life style) as well as the near cessation of training during that time. It is rare for me to see scores in the high 60’s and low 70’s but it dipped that low several times over the last two weeks.

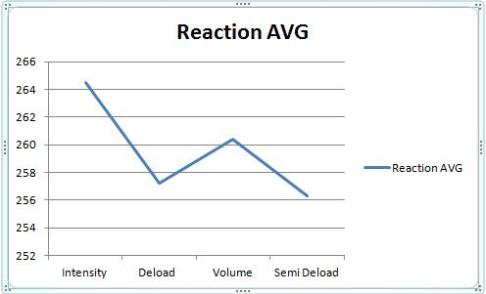

For more effect I’ve added a weekly mean trend and my ithlete screen shots below.

There is a clear downward trend over the 4 week period. The result of which can be attributed to several factors, not just the travel aspect. Obviously, with more preparation and more effort, I could have minimized these effects and maintained my training. It goes without saying that competitive athletes will likely have much more structure to their transitioning from one time zone to another to reduce the negative effects as much as possible.

So, from my experience and based on the limited research on the topic, it appears that; a) response to travel stress is individual and b) when considered with subjective measures of fatigue, HRV may serve as a useful tool for reflecting the effects of travel and the associated period of adaptation.

References

Botek, M., Stejskal, P., & Svozil, Z. (2010). Autonomic nervous system activity during acclimatization after rapid air travel across time zones: A case study. Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis. Gymnica, 39(2), 13-21.

Dranitsin, O. V. (2008). The effect on heart rate variability of acclimatization to a humid, hot environment after a transition across five time zones in elite junior rowers. European Journal of Sport Science, 8(5), 251-258.

Tateishi, O., & Fujishiro, K. (2002). Changes in circadian rhythms in heart rate parasympathetic nerve activity after an eastward transmeridian flight. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 56, 309-313.

Tateishi, O. et al. (2000). Autonomic nerve tone after an eastward transmeridian flight as indicated by heart rate variability. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 5(1), 53–59.