Our “stability” paper has recently been published in Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cpf.12233/abstract

ABSTRACT

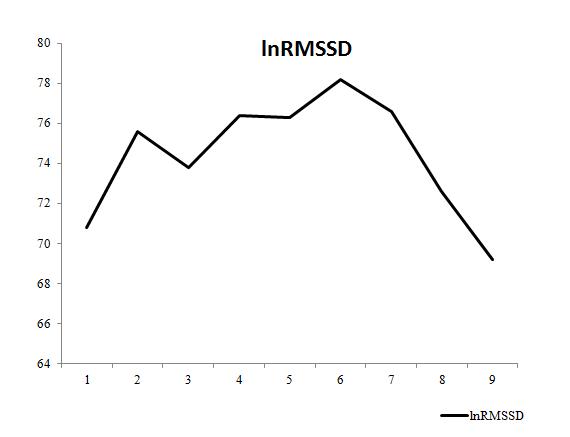

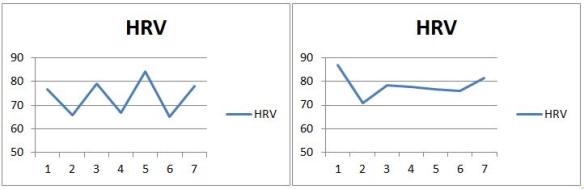

Resting heart rate variability (HRV) is a potentially useful marker to consider for monitoring training status in athletes. However, traditional HRV data collection methodology requires a 5-min recording period preceded by a 5-min stabilization period. This lengthy process may limit HRV monitoring in the field due to time constraints and high compliance demands of athletes. Investigation into more practical methodology for HRV data acquisition is required. The aim of this study was to determine the time course for stabilization of ECG-derived lnRMSSD from traditional HRV recordings. Ten-minute supine ECG measures were obtained in ten male and ten female collegiate cross-country athletes. The first 5 min for each ECG was separately analysed in successive 1-min intervals as follows: minutes 0–1 (lnRMSSD0–1), 1–2 (lnRMSSD1–2), 2–3 (lnRMSSD2–3), 3–4 (lnRMSSD3–4) and 4–5 (lnRMSSD4–5). Each 1-min lnRMSSD segment was then sequentially compared to lnRMSSD of the 5- to 10-min ECG segment, which was considered the criterion (lnRMSSDCriterion). There were no significant differences between each 1-min lnRMSSD segment and lnRMSSDCriterion, and the effect sizes were considered trivial (ES ranged from 0·07 to 0·12). In addition, the ICC for each 1-min segment compared to the criterion was near perfect (ICC values ranged from 0·92 to 0·97). The limits of agreement between the prerecording values and lnRMSSDCriterion ranged from ±0·28 to ±0·45 ms. These results lend support to shorter, more convenient ECG recording procedures for lnRMSSD assessment in athletes by reducing the prerecording stabilization period to 1 min.

In collaboration with Dr. Fabio Nakamura, we have a new paper currently in review that assesses the suitability of ultra-short (60-s) measures with minimal stabilization in elite team-sport athletes using the Polar system. We will also be assessing if these modified HRV recording procedures sufficiently reflect changes in fitness after a training program. Overall, shortened lnRMSSD recording procedures appear very promising. This will hopefully enhance the practicality of HRV monitoring among sports teams.