Though I’m currently a solid 17 hour drive away from home, I still correspond with several athletes I formerly worked with prior to my relocation. I’ve got a few athletes sending me their ithlete data every week. I finally had time to sit down and analyze some of it and so today I’ll present and discuss the past four weeks worth of data from a high school football player.

Basic Descriptors

This athlete is currently a high school sophomore and will be the starting Quarterback for his high school Varsity Football Team. In addition to high school football, this athlete is also competing in track and field (Javelin, Shot Put and Triple Jump) and summer football.

Monitoring Variables

HRV: The athlete measures HRV with ithlete in a standing position every morning after waking and bladder emptying.

Subjective Sleep Score: Following his HRV measurement, sleep was rated (1-5 scale) and comments were entered regarding the previous days events on the ithlete app.

sRPE: I also asked the athlete to provide a rating of perceived exertion score after each training session, practice or competition (1-10 scale) and input this into the ithlete training load feature. This is not multiplied by session duration.

Reaction Test: Lastly, the athlete performed a simple reaction test with this application after ithlete to assess psycho-motor speed.

My rationale for the selected variables is quite simple:

- These tools/metrics are simple, inexpensive and non-invasive

- The total time required to complete these is between 3-5 minutes each day. Keeping them easy and quick helps with compliance which as you’ll see, was a non-issue for this athlete.

- I wanted both objective and subjective markers

- The Reaction test often gets talked about but rarely do I see any data. After having some personal success with it I decided to test it out with him.

4 Weeks of Data and Analysis

The following data is from the last 4 weeks where the athletes Track&Field and Football schedules overlapped, resulting in a significant increase in physical stress. I have no influence on his current training, schedule, etc. and therefore this analysis is entirely retrospective. Furthermore, I always recommend that training and life style remain unchanged when people start using ithlete. After a few months of training we then analyze the data and determine what course of action to take from there. By making training/life style manipulations right from the start it will be hard to determine how effective they may be. With that said, the data is presented below, broken down into each constituent week.

*Note: Click images to enlarge. Reaction test results fall under “Tap” in the tables starting in week 2.

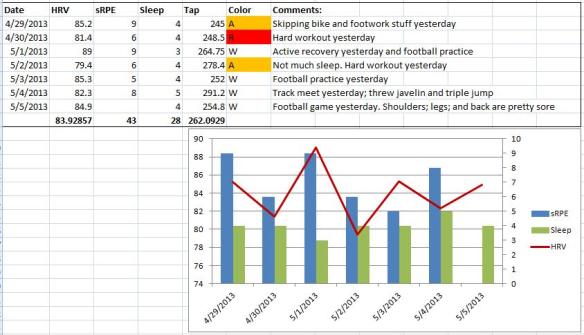

Week 1:

- No Reaction Test data this week, commences in week 2.

- Training appears to be well tolerated all week with a spike in HRV after a rest day followed by a track meet on Saturday 4/28. The track meet appears to be more stressful than is perceived by the athlete based on the 9 point drop.

- Training load weekly sum is 31

- HRV weekly mean is 92.4

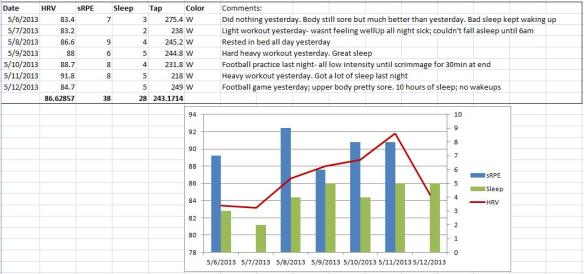

Week 2:

- He appears to be insufficiently recovered from the track meet and persists with intense training. HRV remains below 90 all week while the previous week stayed above 90.

- With some fatigue accumulated he has a track meet on Friday followed by a Football game on Saturday. The trend this week indicates high fatigue compared to the previous week.

- Training load weekly sum increases by 16%.

- HRV weekly mean drops by 8 points; Sleep total drops slightly, First Reaction weekly mean is 262.1

Week 3:

- Poor sleep and high soreness is reported early this week after the very stressful previous week. On 5/7 he stays home from school with cold/flu symptoms.

- He recovers quickly and the rest of the week looks pretty good as his HRV trends back up over 90.

- Football game on Saturday causes a decent drop in HRV. Sunday is a rest day.

- HRV weekly mean improves to 86.6; Training load decreased; Reaction speed decreased (faster).

Week 4:

- HRV peaks at 96 after a much needed day off on Sunday

- 2 Track meets this week with a new personal best throw; perceived training load decreases slightly and HRV started trending up approaching 90.

- HRV weekly mean increases slightly, Sleep quality increases, Reaction Time is similar to previous week (slight increase).

Further Analysis

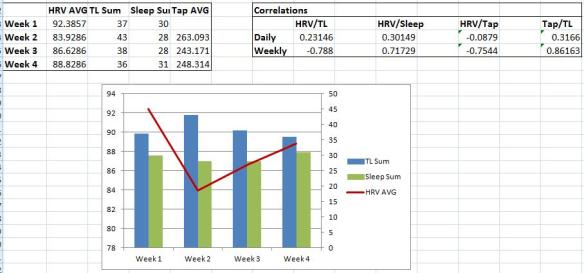

In the screen shot below, I’ve included a table and chart of the weekly mean of HRV and Reaction Time, as well as the weekly sums of Training Load and Sleep score. In the table to the right I’ve calculated some correlations.

Brief Thoughts

This data set supports the theory of monitoring not just the daily, but also the weekly trend changes in HRV. However, keeping tabs on the day to day changes, particularly after intense workouts or competition, can allow for more appropriate training load manipulations to try and influence the weekly changes. This is particularly important during a competitive season where overreaching is not desired. Clearly in this case, the athlete experienced some overreaching after the abrupt increase in physical stress evidenced by his illness, disturbed sleep etc. However, the overreaching was short-term and the consequences short-lived as he quickly recovers. When HRV peaks in week 4 we also see an increase in performance (Track PR). Of course the overreaching easily could have been avoided had he not been trying to train for and compete in two different sports at the same time. However, this is the reality of many high school athletes who try and juggle multiple sports in the same season.

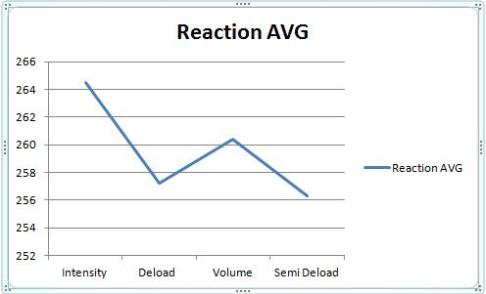

Similar to my experience discussed here, his Reaction test essentially mirrored HRV when the weekly means were calculated. Perceived training load clearly had the biggest effect on these two variables. Unfortunately we didn’t incorporate the Reaction Test until week 2 so keep that in mind when looking at the correlation values as week 1 was not included with Reaction Time.

In this case, I do not believe that the RPE of the competitions provided a good reflection of actual competition stress. In many cases when he had a competition, HRV would decline quite a bit yet the RPE would be moderate. Competing adds another element of stress unaccounted for in these situations which should be considered by coaches.

I believe that this athletes short term overreaching and subsequent illness and sleep disturbances could easily have been avoided. Reacting to the decrease in HRV, increase in Reaction time, increased soreness, poor sleep ,etc. by allowing for more recovery time likely would’ve averted this. However, how this would effect his performance in the following weeks when HRV peaks and he see’s an increase in performance is unknown. After several days of a decreasing trend in HRV, rest should be strongly considered, particularly during competition periods.

The comments section of ithlete was valuable in communicating to me brief details about what in particular may be causing stress. This is an undervalued and underrated feature in my opinion.

HRV and Reaction test weekly mean and perceived training load weekly sum each appear to be sensitive markers of the physical stress load experienced by this athlete. Adjusting training loads appropriately in response to these variables may have prevented the unintentional overreaching and illness experienced by this athlete. From this set of data we can conclude that HRV, Reaction test and perceived exertion ratings were effective markers of training status with this athlete.