Over the next several posts I will attempt to provide a little more depth to the typical explanations of heart rate variability that I’ve provided in the past. I will be displaying ECG data and HRV software screen shots to provide a better visual representation of HRV analysis. I will present and discuss things like;

- How HRV data is often collected and analyzed

- ECG basics

- What respiratory sinus arrhythmia looks like

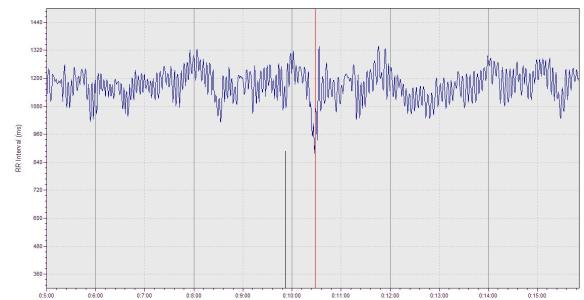

- What an ectopic beat looks like

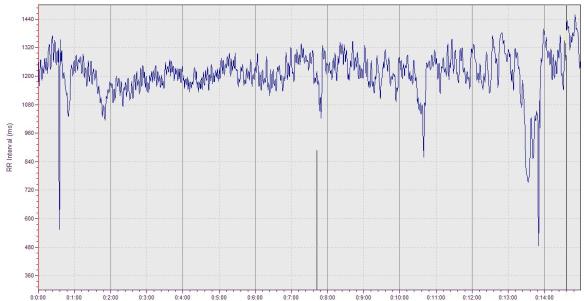

- What a tachogram is and looks like (HRV software)

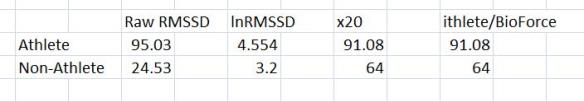

- Comparing athlete to non-athlete ECG/HRV data

- Looking at supine and standing ECG/HRV data

- Looking at paced vs. spontaneous breathing data and how it affects HRV

- Showing how subtle errors can impact an HRV measurement

- Discussing HRV research questions that my colleague and I are investigating here in our lab

- Whatever else seems relevant as I get writing

Today’s post will serve as a brief, but slightly more in depth introduction to heart rate physiology. To really get a handle on HRV, it’s important to have an understanding of the interplay between the brain and heart and the details therein. I encourage interested readers to check out an actual physiology text for a more elaborate and detailed discussion for which I’ll provide a few recommendations at the end.

Heart Rate

The human heart is equipped with an intrinsic pacemaker within the wall of the right atrium called the sinoatrial node (SA node). The SA node randomly depolarizes, generating action potentials that ultimately result in a contraction (heart beat). All heart beats that originate from the SA node are “normal” beats and provide normal cardiac rhythm. However, as we’ll get into eventually when I display some ectopic beats, depolarization also regularly occurs in other areas within the myocardium, which if reach threshold, can initiate a contraction on its own. Non SA node action potentials disturb cardiac rhythm that is ideally dictated by the SA node (more on ectopic beats in future). Left alone, the SA node would give you a resting heart rate of about 100 beats per minute. Obviously, healthy individuals have much lower heart rates while at rest. Other times, we can experience quite high elevations in heart rate to facilitate blood distribution requirements (e.g., during physical activity). We’ll get into how these changes in heart rate occur momentarily.

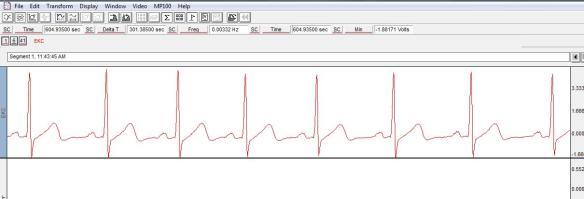

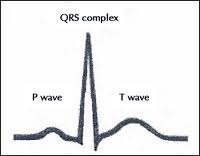

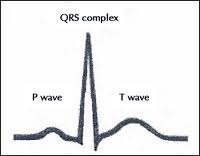

In the lab, we can evaluate heart beat information with electrocardiographic (ECG) recordings. An ECG detects electrical currents at the surface of the skin generated by the action potentials that propagate through the heart. In our lab, since we’re mainly interested in heart rate variability and not intricate ECG analysis, we use a simple, modified lead II electrode placement. From the ECG we can observe 3 distinct patters that represent the electrical conductivity involved in the cardiac cycle;

P wave – Displays as a small upward deflection and represents atrial depolarization. The P wave indicates that the impulse originated from the SA node and therefore results in a “normal” beat.

QRS Complex – Begins with a shallow downward deflection (Q), followed by a tall upward deflection (R) and ends with another downward deflection (S). Collectively, this represents ventricular depolarization.

T wave – Oftend described as dome-shaped in appearance and represents ventricular repolarization

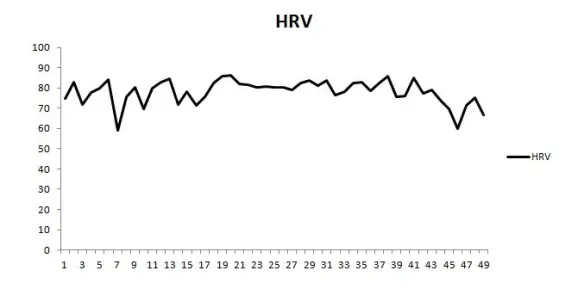

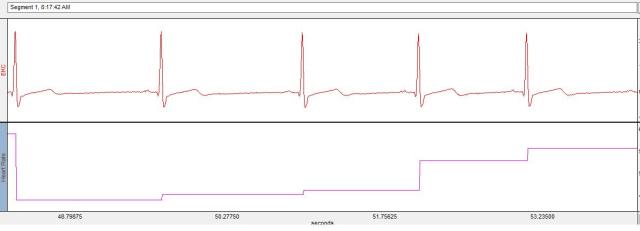

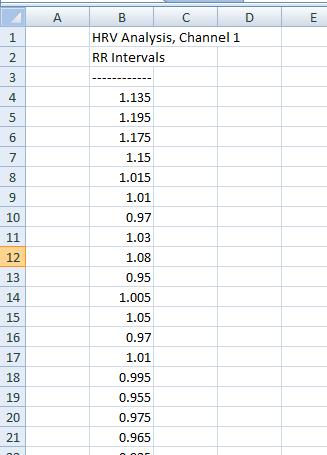

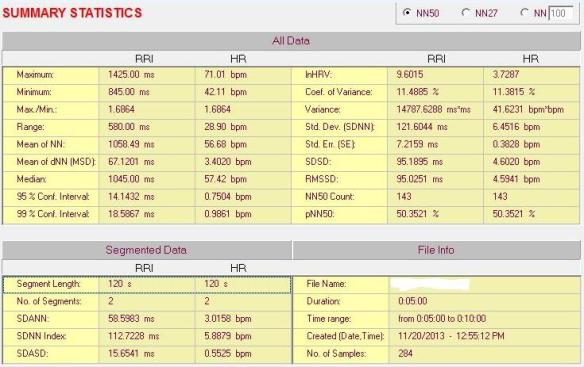

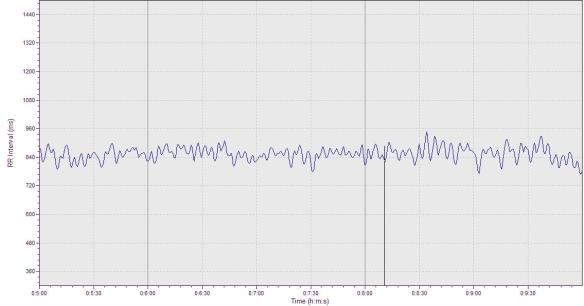

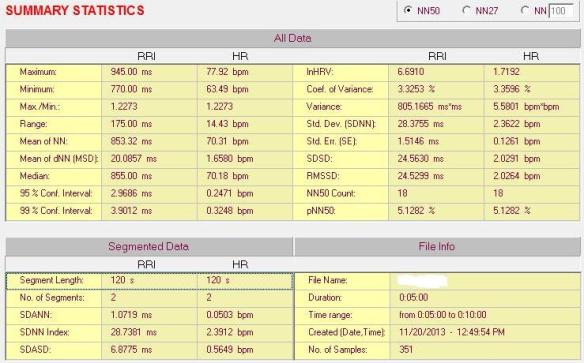

As you can see, the R wave has a high peak making measurements between cardiac cycles rather easy. The elapsed time between two R waves creates an R-R interval. The time between R-R intervals varies across successive R-R intervals and is termed heart rate variability. In the screen shot below of the AcqKnowledge software, notice how the space between R waves (the tall peaks) is inconsistent as some intervals are wider and some are more narrow.

Centrally Mediated Cardiac Control

Now we’ll return to our discussion on heart rate control. Heart rate is influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, however for this discussion, our interest is primarily with central nervous system regulation of cardiac control via autonomic innervations of the heart. Heart rate is largely mediated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic influence which originates in the cardiovascular center of the brain. The cardiovascular center is located on the lower portion of the brain stem at the medulla oblongata. From here, sympathetic neurons extend from the brain, through the spinal cord and directly into the heart. Increased sympathetic activity increases the release of norepinephrine which speeds up SA node depolarization (increases heart rate) and increases the force of contraction. This response occurs to facilitate increased blood distribution requirements that may arise due to physical activity, stress, standing up, etc.

Parasympathetic influence of the heart occurs via the Vagus nerve (10th cranial nerve) which originates in the medulla and has axons that terminate directly into the heart. Vagal stimulation elicits an inhibitory effect on the SA node via release of acetylcholine, effectively reducing heart rate and is associated with “rest and digest” activity. Since vagal activity inhibits SA node activity, vagal withdrawal will result in less SA node inhibition and allow the heart to beat faster. At the onset of exercise, the initial increase in heart rate is a result of vagal withdrawal with a progressive increase in sympathetic activity as exercise persists (Yamamoto et al. 1991).

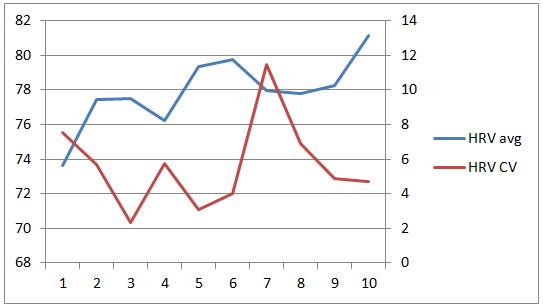

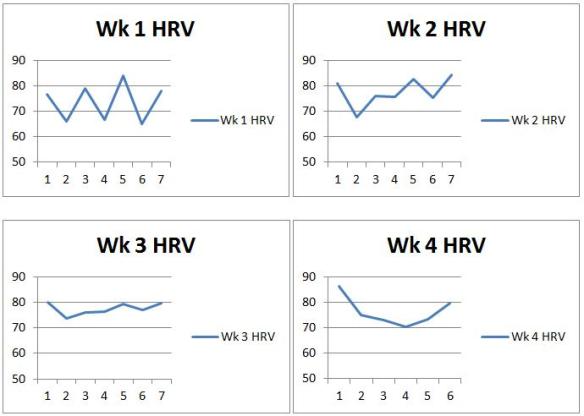

Since heart rate is directly affected by autonomic activity, it serves as a relatively simple marker for us to monitor to assess autonomic status. Increased parasympathetic activity will reduce heart rate and result in greater variability between R waves. In contrast, a higher heart rate with less variability (think more metronomic) is the result of reduced parasympathetic activity and possibly increased sympathetic activity. HRV has thus become a valuable metric to monitor in athletes as it provides information regarding the relative balance of “stress” in the individual. Though I’m a proponent of HRV monitoring in athletes, its interpretation requires caution as nothing is black and white when it comes to determining an athlete’s training status from HRV, particularly from isolated measurements. Rather, taken with performance trends, psychometrics (perception of mood, soreness, fatigue, etc.), and training load, HRV becomes more meaningful.

In the next post, I will start to get into HRV analysis with some software screenshots to provide a good visual representation of HRV.

References/Recommended Reading:

Smith, D. & Fernhall, B. (2010) Advanced Cardiovascular Exercise Physiology. Human Kinetics. http://www.amazon.com/Advanced-Cardiovascular-Exercise-Physiology/dp/0736073922

Tortora, G. & Derrickson, B. (2006) Principles of Anatomy and Physiology 11th Edition. Biological Sciences Textbooks Inc.

Yamamoto, Y., Hughson, R. L., & Peterson, J. C. (1991). Autonomic control of heart rate during exercise studied by heart rate variability spectral analysis. Journal of Applied Physiology, 71(3), 1136-1142.