Here are 5 new studies pertaining to HRV and training.

Previous Edition: Vol: 1

1.

Sartor, F. et al. (2013) Heart rate variability reflects training load and psychophysiological status in young elite gymnasts. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, Published ahead of print.

Abstract

In gymnastics monitoring of the training load and assessment of the psychophysiological status of elite athletes is important for training planning and to avoid overtraining, consequently reducing the risk of injures. The aim of this study was to examine whether heart rate variability (HRV) is a valuable tool to determine training load and psychophysiological status in young elite gymnasts. Six young male elite gymnasts took part in a 10 week observational study. During this period, beat to beat heart rate intervals were measured every training day in week 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9. Balance, agility, upper limb maximal strength, lower limb explosive and elastic power were monitored during weeks 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10. Training load of each training session of all 10 weeks was assessed by session-RPE and psychophysiological status by Foster’s index. Morning supine HRV (HF% and LF%/ HF%) correlated with the training load of the previous day (r=0.232, r=-0.279, p<0.05 ). Morning supine to sitting HRV difference (mean RR, mean HR, HF%, SD1) correlated with session-RPE of the previous day (r=-0.320, r=0.301 p<0.01, r=0.265, r=-0.270, p<0.05) but not with Foster’s index. Training day/reference day HRV difference (mean RR, SD1) showed the best correlations with session-RPE of the previous day (r=-0.384, r=-0.332, p<0.01) and Foster’s index (r=-0.227, r=-0.260, p<0.05). In conclusion, HRV, and in particular training day/reference day mean RR difference or SD1 difference, could be useful in monitoring training load and psychophysiological status in young male elite gymnasts.

2.

Boutcher, S.H. et al. (2013) The relationship between cardiac autonomic function and maximal oxygen uptake response to high-intensity intermittent exercise training. Journal of Sports Sciences, Published ahead of print.

Abstract

Major individual differences in the maximal oxygen uptake response to aerobic training have been documented. Vagal influence on the heart has been shown to contribute to changes in aerobic fitness. Whether vagal influence on the heart also predicts maximal oxygen uptake response to interval-sprinting training, however, is undetermined. Thus, the relationship between baseline vagal activity and the maximal oxygen uptake response to interval-sprinting training was examined. Exercisers (n = 16) exercised three times a week for 12 weeks, whereas controls did no exercise (n = 16). Interval-sprinting consisted of 20 min of intermittent sprinting on a cycle ergometer (8 s sprint, 12 s recovery). Maximal oxygen uptake was assessed using open-circuit spirometry. Vagal influence was assessed through frequency analysis of heart rate variability. Participants were aged 22 ± 4.5 years and had a body mass of 72.7 ± 18.9 kg, a body mass index of 26.9 ± 3.9 kg · m−2, and a maximal oxygen uptake of 28 ± 7.4 ml · kg−1 · min−1. Overall increase in maximal oxygen uptake after the training programme, despite being anaerobic in nature, was 19 ± 1.2%. Change in maximal oxygen uptake was correlated with initial baseline heart rate variability high-frequency power in normalised units (r = 0.58; P < 0.05). Thus, cardiac vagal modulation of heart rate was associated with the aerobic training response after 12 weeks of high-intensity intermittent-exercise. The mechanisms underlying the relationship between the aerobic training response and resting heart rate variability need to be established before practical implications can be identified.

3.

James, DVC. Et al (2012) Heart Rate Variability: Effect of Exercise Intensity of Post-Exercise Response. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport. 83(4)

Abstract:

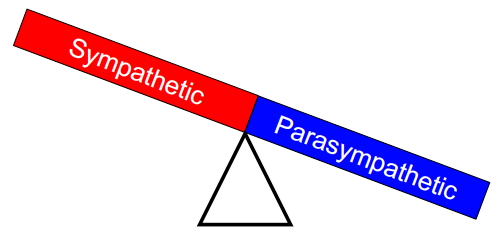

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the influence of two exercise intensities (moderate and severe) on heart rate variability (HRV) response in 16 runners 1 hr prior to (-1 hr) and at +1 hr, +24 hr, +48 hr, and +72 hr following each exercise session. Time domain indexes and a high frequency component showed a significant decrease (p < .001) between -1 hr and +1 hr for severe intensity. The low frequency component in normalized units significantly increased (p < .01) for severe intensity at +1 hr. Only severe exercise elicited a change in HRV outcomes postexercise, resulting in a reduction in the parasympathetic influence on the heart at +1 hr; however, values returned to baseline levels by +24 hr.

4.

Gravitis, U. et al (2012) Correlation of basketball players physical condition and competition activity indicators. Lase Journal of Sports Science, 3(2): 39-46

Abstract

We failed to find any research about whether physical condition affects the indicators of a basketball player’s competition activity, and if yes, then to what extent; whether there is direct correlation between the indicators of a basketball player’s physical condition and his shooting accuracy in a game, as well as the number of obtained and lost balls by him.

Aim of the research: to investigate correlation of basketball players’ indicators of physical condition and competition activity.

Male basketball players aged 21-25 years participated in the research. On the pre-game day all basketball players were tested. Players’ heart rate was interpreted with the scientific device Omega M. A computer gave conclusion about a player’s degree of tension, as well as the degree of adaptation to physical loads, the readiness of the body energy provision system, the degree of the body training and the psycho-emotional condition, as well asthe total integral level of sports condition at the given moment. On the next day of the competition calendar game the content analysis of the competition technical recording was made to compare the player’s whose physical indicators were lower performance with his average performance in the whole tournament. Altogether 80 cases have been analysed when a player having lower physical condition indicators participated in a game.

All in all the players having lower indicators of physical condition in 80% of cases competition activity results were lower than their average performance in the tournament. The Pearson’s rank correlation coefficient also shows a close connection between the indicators of physical condition and competition activity (r=0.687; p<0.01), in comparison to a player’s average performance during the whole tournament. Basketball players’ indicators of physical condition have close correlation (r=0.687; p<0.01) with the indicators of competition activity.The results of physical condition test obtained with the help of the device Omega M can be used to anticipate basketball players’ performance of their competition activity.

5.

Chalencon S, Busso T, Lacour J-R, Garet M, Pichot V, et al. (2012) A Model for the Training Effects in Swimming Demonstrates a Strong Relationship between Parasympathetic Activity, Performance and Index of Fatigue. PLoS ONE 7(12): e52636. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052636

Abstract

Competitive swimming as a physical activity results in changes to the activity level of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). However, the precise relationship between ANS activity, fatigue and sports performance remains contentious. To address this problem and build a model to support a consistent relationship, data were gathered from national and regional swimmers during two 30 consecutive-week training periods. Nocturnal ANS activity was measured weekly and quantified through wavelet transform analysis of the recorded heart rate variability. Performance was then measured through a subsequent morning 400 meters freestyle time-trial. A model was proposed where indices of fatigue were computed using Banister’s two antagonistic component model of fatigue and adaptation applied to both the ANS activity and the performance. This demonstrated that a logarithmic relationship existed between performance and ANS activity for each subject. There was a high degree of model fit between the measured and calculated performance (R2 = 0.84±0.14,p<0.01) and the measured and calculated High Frequency (HF) power of the ANS activity (R2 = 0.79±0.07, p<0.01). During the taper periods, improvements in measured performance and measured HF were strongly related. In the model, variations in performance were related to significant reductions in the level of ‘Negative Influences’ rather than increases in ‘Positive Influences’. Furthermore, the delay needed to return to the initial performance level was highly correlated to the delay required to return to the initial HF power level (p<0.01). The delay required to reach peak performance was highly correlated to the delay required to reach the maximal level of HF power (p = 0.02). Building the ANS/performance identity of a subject, including the time to peak HF, may help predict the maximal performance that could be obtained at a given time.