Distinguishing functional over-reaching (FOR) from non-function over-reaching (NFOR)can be difficult to do during overload periods; particularly when laboratory measures are inaccessible to the coach or athlete. A common criteria used to determine FOR from NFOR is to assess performance before and after overload training. The fatigue accumulated from the increased training loads will result in expected performance decrements. After an unloading period of 1-2 weeks, performance should return to or exceed pre-overload performance values. An athlete can be considered NFOR if performance remains suppressed after this 2 week period.

Coaches can be proactive in their efforts to avoid NFOR with their athletes by maintaining various monitoring strategies. Keeping tabs on certain variables throughout overload periods allows the coach to detect early warning signs that may indicate excessive fatigue in an athlete(s). Such a metric often discussed is the reaction test. Today I will review some of the available research that investigates the efficacy of the reaction test as a method of potentially determining or indicating NFOR in athletes.

Why The Reaction Test?

The theory behind why the reaction test may serve as a good indicator of overreaching and/or the overtraining syndrome has been postulated by Nederhof et al (2006). Essentially, the overtraining syndrome has several signs and symptoms also seen in chronic fatigue syndrome and major depression. Both chronic fatigue and major depression are associated with slower psychomotor ability. Thus, it is hypothesized that psychomotor speed may be slower in athletes with OTS.

Reaction Test and Overreaching

Nederhof and colleagues (2007) put their theory to the test and evaluated performance, perceived fatigue/mood (RESTQ-sport and POMS) and psychomotor speed (reaction tests) in trained cyclists (n=14) and a control group (n=14). Training load was monitored via sRPE (RPE x session length). Testing was performed at baseline, following a 2 week overload period and once more following a 2 week taper. Of the 14 cyclists, 5 were considered FOR (they fulfilled at least 2 out of the three objective criteria in combination with at least 1 subjective criterion during the second but not during the third exercise test) and 7 were considered well trained (WT) while the remaining 2 were excluded.

Two reaction tests were used. The first described test was the “Finger Pre-Cuing Task” that required the individual to react to a prompt by pressing the correct keys on a computer. The other test was the “Determination Test” that required either manual of pedal reaction in response to visual or auditory stimuli also on a computer. Full descriptions of these tests can be read in the full text here.

The control group and the WT group improved their reaction time at each test. The FOR group however showed increased (slower) reaction time after the overload period but improved reaction time beyond baseline values after the taper. Regarding statistical significance the authors stated; “After high load training the FO group was 20% slower than the control group and 8% slower than theWT group. For comparison, patients with major depression are 20 to 26% slower than healthy controls [21,32] and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome are 15% slower than healthy controls [21]. Thus, although not statistically significant, differences in the present study are meaningful“.

Rietjans et al (2005) aimed to determine if a combination of test parameters could help detect overreaching in 7 well trained male cyclists. Over a 2 week period, training load was doubled while intensity was increased by 15%. Values for the following tests/assessments were collected pre and post training period: Maximal incremental cycle ergometer test with continuous ventilatory measurements and blood lactate values, time trial, basal blood parameter tests, hormones (GH, IGF-1, ACTH, neuro-endocrine stress test, shortened POMS, RPE and a cognitive reaction time test.

The results: “A novel finding was that reaction times increased significantly, indicating that overreaching might adversely affect speed of information processing by the brain, especially for the most difficult conditions. After the intensified training period, neither changes in exercise-induced plasma hormone values, nor SITT values were observed. During the CAPT only cortisol showed a significant decrease after the intensified training period. Hemoglobin showed a significant decrease after the intensified training period whereas hematocrit, red blood cell count (RBC) and MCV tended to decrease. The intensified training had no effect on physical performance (Wmax or time trial), maximal blood lactate, maximal heart rate and white blood cell profile. The most sensitive parameters for detecting overreaching are reaction time performance (indicative for cognitive brain functioning), RPE and to a lesser extend the shortened POMS. This strongly suggests that central fatigue precedes peripheral fatigue. All other systems, including the neuro-endocrine, are more robust and react most likely at a later stage in exhaustive training periods.”

Reaction Test and Perceived Performance

Nederhof and colleagues (2008) set out to determine if reaction tests are related to perceived performance in rowers. On 5 occasions over the course of a season, reaction tests were performed along with perceived performance measures (“Reduced Sense of Accomplishment” scale from the Athlete Burnout Questionaire) in varsity rowers. The same two reaction tests (Finger Pre-Cueing and the Determination Test) described above were used. The results showed that a significant relationship between the Determination Test and perceived performance. The authors stated; “…rowers who scored higher on the ‘‘Reduced Sense of Accomplishment’’ scale of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire had longer reaction times on the determination test. For every point the rowers scored higher, their reaction times were 18 ms longer on the action mode and 12 ms on the reaction mode of the determination test. This effect was not found for the finger pre-cueing task.”

Though their hypothesis was supported, the authors affirm that several practical issues require resolution.

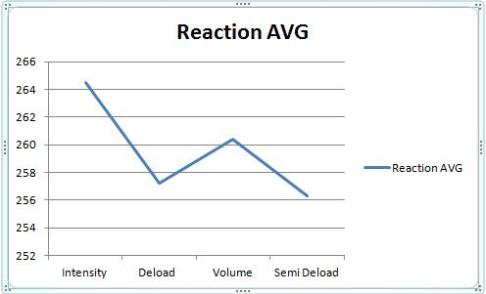

My Reaction Test Data Compared to HRV over 4 Different Training Periods

For a much more elaborate discussion on this experiment you can see the original post here. Essentially what I found was that Reaction test average and HRV average mirrored each other at each training period. HRV decreased and Reaction time increased (slower) during High Intensity and again during High Volume training reflecting fatigue. During reduced training loads HRV increased and Reaction time decreased (faster).

Considerations and Limitations

The reaction test appears to be a test worthy of consideration for coaches looking to incorporate monitoring variables into their training regime. The following is a list of factors to keep in mind regarding this test:

• Caffeine has a well-established effect on reaction time and should therefore be controlled for when implementing reaction testing

• Psychological factors can impact the effectiveness and reliability of the test. Though this is an objective test, the effort put forth by the athlete may not be consistent. Since this test is sensitive to small changes in reaction time, this can obscure data and thus interpretation.

• As with HRV, it is probably best to experiment with a reaction test with a small sample of athletes to determine its usefulness before trying to implement with an entire team.

• Just like any other monitoring variable, reaction time should be considered with other factors when attempting to draw meaningful interpretations from the results.

Reaction time test results appear to respond early to fatigue during overload training. Reaction times (test dependent) may correlate with perceived performance. The simplicity, practicality, affordability and non-invasiveness of a reaction test make it appealing to coaches as a field test.

References

Nederhof, E., et al. (2006) Psychomotor speed: possibly a new marker for overtraining syndrome. Sports Medicine, 36(10): 817-28.

Nederhof, E., Lemmink, K., Zwerver., J. & Mulder, T. (2007) The effect of high load training on psychomotor speed. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 28: 595-601.

Nederhof, E., Visscher, C. & Lemmink, K. (2008) Psychomotor speed is related to perceived performance in rowers. European Journal of Sport Science, 8(5): 259-265

Rietjans, GJ., et al. (2005) Physiological, biochemical and psychological markers of strenuous training induced fatigue. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(1): 16-26.