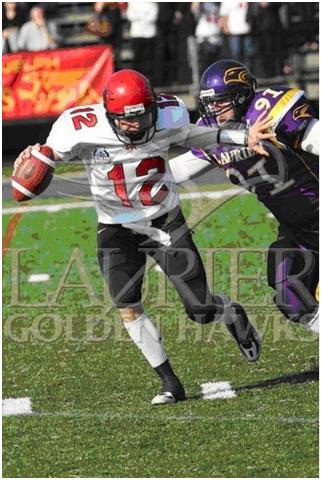

Monitoring athletes throughout training provides coaches with extremely valuable information regarding each athlete’s responsiveness to imposed training loads. Most would agree that the main objective for any coach (at competitive levels) is to win. If you fail to do this you will likely be fired.

I think we can also agree that bringing our athletes to peak physical condition (as it applies to their sport) will increase our chances of winning. To do this effectively, physical preparation in both team practice and S&C must be balanced. The right balance of training loads will yield optimal adaptation.

Adaptation is Key

Training (technical and physical) is a stressor our athletes must recover from. If the stress is too great, adaptation will be compromised. If the stress is insufficient, improvements will not take place. Therefore, the training stimulus must be within our athlete’s ability to adapt, allowing for performance improvements. This is pretty well understood by most coaches. However, the ability to balance loads effectively is much less understood. Too often coaches rely on pre-planned training regime’s that fail to take into account each athletes individual adaptive capacity. It is the coach’s responsibility to critically evaluate several issues that arise throughout the year such as;

- Why did an athlete get hurt?

- Why did an athlete fall ill?

- Why is the team seeing decrements in performance?

- Why are we not performing to our abilities throughout the entire match?

- Why are certain athletes improving while others are regressing?

I’m sure you can think of more questions to consider.

Monitoring HRV in Sports Teams

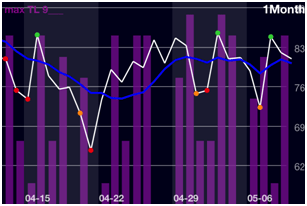

Hap, Stejskal & Jakubec (2010) set out to monitor the HRV of 8 competitive male volley ball players (approximately 18-25 years old) over a 7 day microcycle during training camp. The 7 day camp had the athletes partake in 11-13 volleyball practices and 14-16 conditioning sessions. The training was entirely pre-planned and HRV scores were not shared with players or coaches. HRV was measured once each day for a total of 7 times (6 measurements were performed in the morning immediately after waking and 1 measurement was performed under controlled conditions in the afternoon).

The results showed 2 athletes demonstrated above average ANS activity (high HRV) throughout the entire week. In these athletes, the load was below training capacity and higher training levels could have been tolerated to further increase performance. In 4 athletes, HRV scores decreased to the lower end of average. This indicates a moderate level of fatigue and that training load corresponded to their training capacities. In the last 2 athletes, HRV scores were negative (below average). Training stress was too high in these individuals and reduced loads and recovery/regeneration modalities would’ve increased the quality of their training.

In this instance, the pre-planned training program was appropriate for 50% of the team. 25% were overtrained and 25% were undertrained.

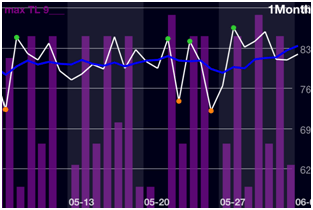

In another study, Cipryan & Stejskal (2010) decided to monitor the HRV of competitive hockey players. There were 18 subjects, 8 were junior level players (18 years old) and 10 were from the adult team (mid-20’s). Both teams underwent their own training and practice programs. HRV was measured twice per week in the morning (Mon and Fri) throughout the 2 month training program.

The results show that from the junior team, 2 players showed above average adaptation capacity. 1 player showed decreased HRV scores indicating high fatigue. Training was appropriate for 5/8 players. In the adult men’s team, 3 players showed higher HRV suggesting that more (volume or intensity) training would’ve been tolerated. 1 player showed decreased HRV. This player could not see an increase in HRV back to baseline levels because the training did not conform to his adaptive abilities. This player was at risk of more frequent health complications. This training program was appropriate for 60% of the team. 30% was undertrained and 10% was overtrained.

In the discussion, the authors proposed that athletes be separated into groups during training with 3 separate programs available. One program for athletes with low HRV (decreased loads) one program from athletes responding appropriately (moderate loads) and one program for athletes with high HRV (increased loads).

The last study that I’ll discuss has been mentioned before in previous articles that I’ve written. Cipryan et al. (2007) measured HRV in Czech U-17 male hockey players once per week in the morning over a 3-5 month period. In addition, the coaches were asked to rate each players performance on a scale of 1-10. The researchers found that as HRV increased, performance was rated better and correlated to more playing time. When HRV was low performance was rated lower. Performance correlated with HRV score.

Thoughts

What I found interesting was that in 2 of the above studies, HRV was monitored only once or twice per week and was still able to provide important data regarding training status. This makes the application of HRV in a team setting much more realistic. Daily measurements can certainly be done and would likely provide more accurate data but can prove to be difficult. The ability to perform HRV measurements are limited by; having access to valid and reliable measuring devices; having a qualified individual(s) to record and analyze data; having athletes capable of following measurement instructions. HRV applications on smart phones certainly would make this process much easier. These are much more cost effective and convenient.

It appears that pre-planned training certainly isn’t optimal for realizing athletic potential in athletes. Though this is very inconvenient for the coach, having the ability to adjust training prescription for certain athletes based on HRV can increase the quality of training and adaptation while decreasing health complications (illness, injury, overtraining).

How often do coaches punish players for poor performance with intense conditioning in practice sessions following a previous competition? How many coaches punish teams with physical conditioning due to team rule infractions? How often are ill or injured players returning to training and competition before they’re ready? Clearly these strategies require some re-evaluation. It is quite possible your training program, no matter how good it looks on paper, is only appropriate for 50-60% of your players.

References

Cipryan, L. & Stejskal, P. (2010) Individual training in team sports based on ANS activity assessments. Medicina Sportiva, 14(2): 56-62

Cipryan, L., Stejskal, P., Bartakova, O., Botek, M., Cipryanova, H., Jakubec, A., Petr, M., & Řehova, I. (2007) Autonomic nervous system observation through the use of spectral analysis of heart rate variability in ice hockey players. Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis. Gymnica, 37(4): 17-21.

Hap, P., Stejskal, P. & Jakubec, A. (2010) Volleyball players training intensity monitoring through the use of spectral analysis of HRV during a training microcycle. Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis. Gymnica, 41(3): 33-38