At this point, most of you are aware that a single HRV (lnRMSSD) score taken in isolation does not necessarily imply or reflect an acute change in performance, fatigue, recovery, etc (though it may sometimes).

Here’s why:

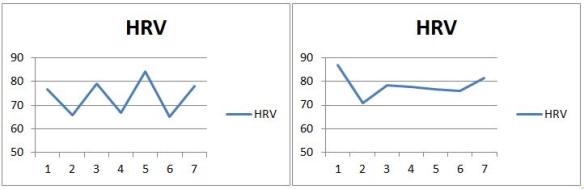

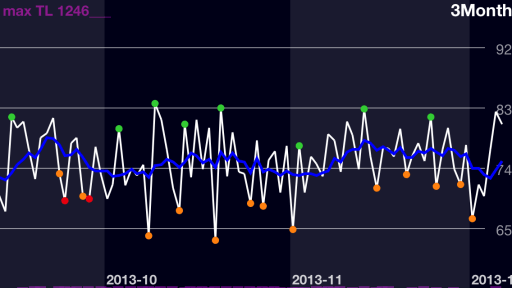

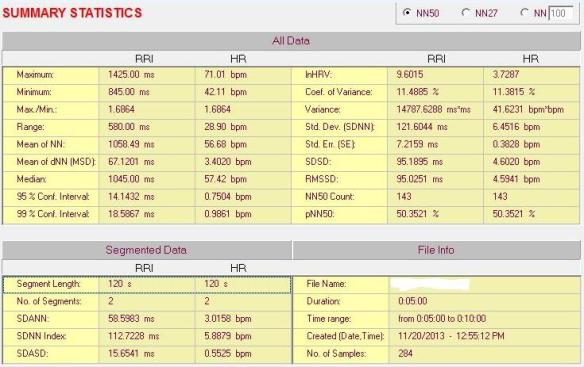

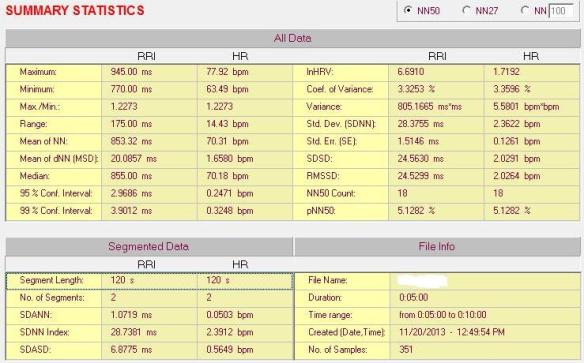

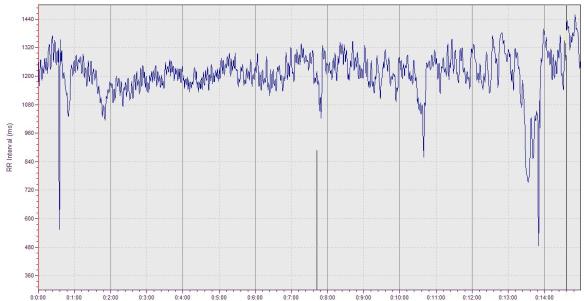

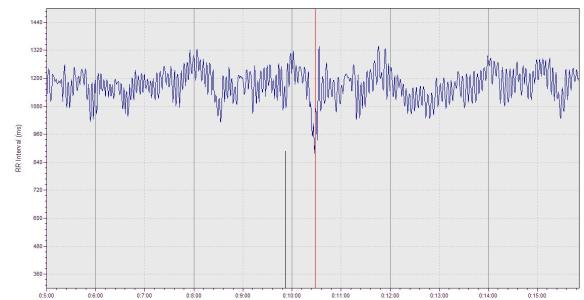

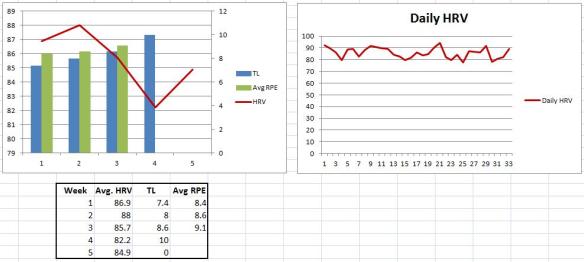

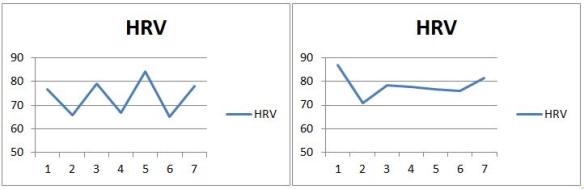

Below are two separate HRV trends I pulled from a training cycle I did last year at week 1 and week 8.

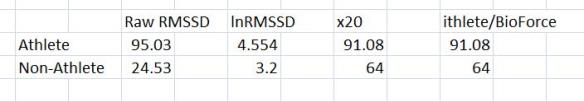

If someone were taking once per week recordings, or pre and post training phase recordings on isolated days, you can see how they can get entirely different results based on which day they measured. Suppose measures were taken on Friday’s from the above trends. These values are 84 and 76.7, respectively. However, if we look at the weekly mean values, we would get 73.6 and 78.3. From the isolated readings, one would conclude that HRV decreased nearly 10 points. However, the weekly mean shows an entirely different change (HRV actually increased from 73.6 to 78.3). Therefore, it’s quite clear that when averaged weekly, HRV scores allow for more meaningful interpretation.

| |

Isolated Measure (Friday) |

Weekly Mean |

| Week 1 |

84 |

73.6 |

| Week 8 |

76.7 |

78.3 |

See the following papers for more on weekly mean vs. isolated recordings (Le Meur et al. 2013; Plews et al. 2012; Plews et al. 2013)

One limitation of the weekly mean value is that is does not reflect the fluctuation in scores throughout the 7 day period. A simple way of determining this is to calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) from the 7 day HRV values (see Plews et al. 2012 for more on CV).

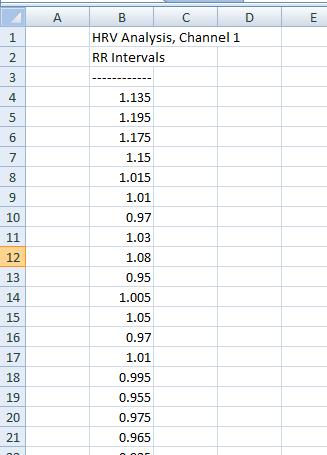

The coefficient of variation is calculated as follows;

CV = (Standard Deviation/Mean)x100

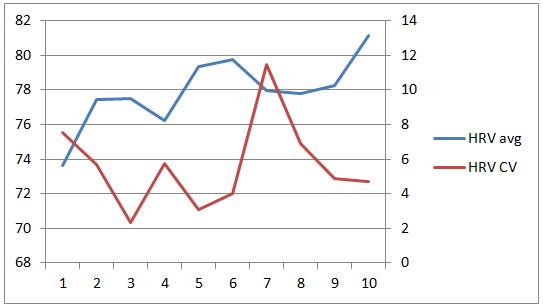

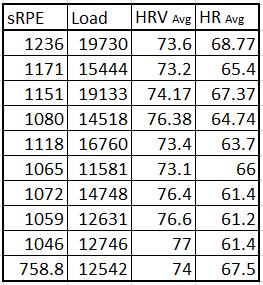

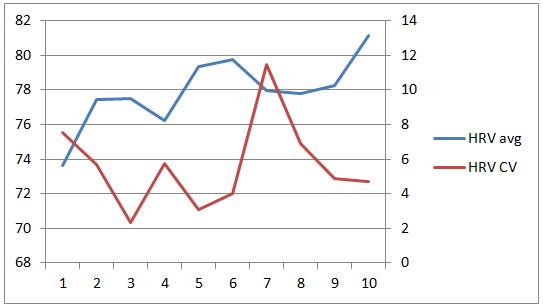

Below is 9 weeks worth of data from a training cycle I performed early last year that resulted in some personal records (PR’s) and was discussed in this post. This time, in addition to the weekly mean values I have also calculated the CV for each week.

Without going into too much detail about the training cycle (see the original post for that), I will highlight a few keep observations.

| HRV Avg |

HRV CV |

Brief Notes |

| 73.6 |

7.5 |

1st week after detraining, Good |

| 77.4 |

5.6 |

Good |

| 77.5 |

2.3 |

Good |

| 76.2 |

5.7 |

Stress, poor sleep, deload |

| 79.37 |

3.0 |

Good |

| 79.7 |

4.0 |

Good |

| 77.9 |

11.4 |

Stressful week |

| 77.8 |

6.8 |

↑ intensity, ↓ Volume, Good |

| 78.2 |

4.8 |

PR(1RMs) |

| 81.1 |

4.7 |

Deload, Good |

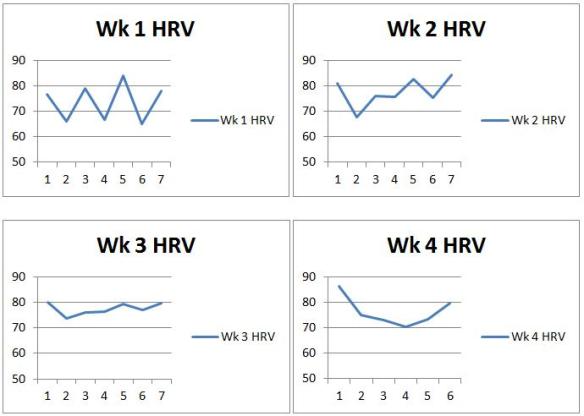

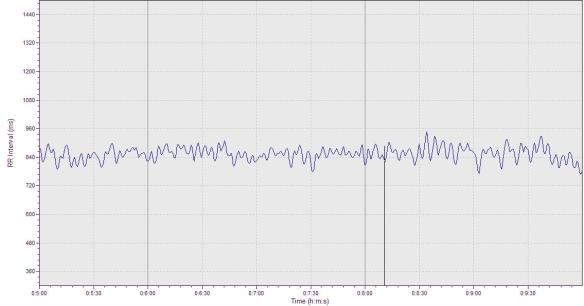

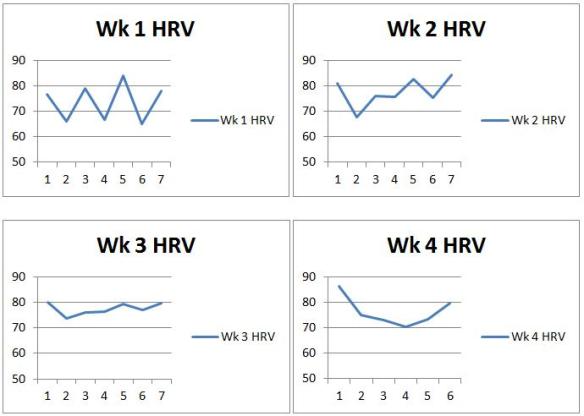

Below are the HRV trends from Week 1 – 4 of the cycle.

Week 1 was my first week training after about 10 days off from lifting (Christmas holidays). Clearly the trend from week 1 reflects the fatigue and recovery as I lifted on M W F that week. On week 2 I performed the same workouts on the same days but with a little more weight for each set. However, it appears (based on CV) that this may have been less stressful. In week 3, I moved to lifting 4 days/week with moderate loads and CV decreases further. Interestingly, the following week (week 4), the weights feel heavy, I feel pretty rough and I take an unplanned deload (CV increases, mean decrease).

Further analysis of the CV and weekly mean can include calculating the smallest worthwhile change (see Buchheit, 2014) to see if a change is practically meaningful. (Will do this in the future once I figure out how to display SWC on a chart).

The point of this post was to introduce the CV concept for those who may not be familiar. I believe that the CV likely provides information regarding stress, fatigue and adaptation that the weekly mean may not reflect. Therefore, the CV and mean values should be considered together.

References:

Buchheit, M. (2014). Monitoring training status with HR measures: do all roads lead to Rome? Frontiers in physiology, 5. http://journal.frontiersin.org/Journal/10.3389/fphys.2014.00073/full

Le Meur, Y., Pichon, A., Schaal, K., Schmitt, L., Louis, J., Gueneron, J., … & Hausswirth, C. (2013). Evidence of parasympathetic hyperactivity in functionally overreached athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 45(11), 2061-2071.

Plews, D. J., Laursen, P. B., Kilding, A. E., & Buchheit, M. (2012). Heart rate variability in elite triathletes, is variation in variability the key to effective training? A case comparison. European journal of applied physiology, 112(11), 3729-3741.

Plews, D. J., Laursen, P. B., Kilding, A. E., & Buchheit, M. (2013a). Evaluating training adaptation with heart-rate measures: a methodological comparison. International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance, 8(6).